[Update 05.04.13: A longer version of this post, with revised results, has evolved into a full-fledged article published by the UK Royal Society. To cite the article: A. A. Casilli, F. Pailler, P. Tubaro (2013). Online networks of eating disorder websites: why censoring pro ana might be a bad idea, Perspectives in Public Health , vol. 133, n.2, p. 94 95. As part of our research project ANAMIA (Ana-mia Sociability: an Online/Offline Social Networks Approach to Eating Disorders), the post has been featured in a number of media venues, including The Economist, Libération, Le Monde, Boing Boing, The Huffingtonpost, CBC Radio Canada, DRadio Wissen, Voice of Russia.]

Tumblr, Pinterest and the toothpaste tube

On February 23rd, 2012 Tumblr announced its decision to turn the screw on self-harm blogs: suicide, mutilation and most prominently thinspiration – i.e. the ritualized exchange of images and quotes meant to inspire readers to be thin. This cultural practice is distinctive of the pro-ana (anorexia nervosa), pro-mia (bulimia) and pro-ED (eating disorders) groups online: blogs, forums, and communities created by people suffering from eating-related conditions, who display a proactive stance and critically abide by medical advice.

A righteous limitation of harmful contents or just another way to avoid liability by marginalizing a stigmatized subculture? Whatever your opinion, it might not come as a surprise that the disbanded pro-ana Tumblr bloggers are regrouping elsewhere. Of all places, they are surfacing on Pinterest, the up-and-coming photo-sharing site. Here’s how Sociology in Focus relates the news:

Thinspiration on Pinterest ranges from photos of stereotypically attractive women, quotes about how good it feels to work out, or a combination of both. I found one quote that says, “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” Another one, with a picture of a thin, almost naked woman says, “What you eat in private, you wear in public.” Finally, I saw a picture with another barely dressed, thin woman that says, “It takes 4 weeks for you to notice your body changing, 8 weeks for your friends and 12 for the rest of the world. Don’t quit.” You cannot log onto Pinterest with out seeing these types of thinspiration show up. Not only are these women posting thinspiration to shame their own inadequacies in their bodies but also with Pinterest, these images get repined for all of their followers to see so they know too that their bodies are inadequate.

Alexa Megna, The Pinterest Problem, Sociology in Focus, March 29, 2012.

Albeit the tone of the post might sound genuinely judgemental, it points out the classical toothpaste tube effect of Internet content policing: if you “squeeze” controversial images and comments from one service, they outflow and relocate elsewhere.

Does censorship work?

For the last three years I’ve been serving as the scientific coordinator of the ANAMIA research project, studying online pro-ED websites and their social determinants. One thing we had to face from the beginning of our inquiry is that so-called pro-ana and pro-mia websites have been around since the early 2000 (see our latest article Ten Years of Ana, published in the March 2012 issue of the journal Social Science Information). They have a history of migrating frequently to avoid censorship. Moreover, censorship obtains the paradoxical outcome of multiplying them, mainly because bloggers and forum administrators feel the urge to duplicate and triplicate their contents for backup purposes: they don’t want to lose months of hard work because some Web host’s pulled the plug on the their page or forum.

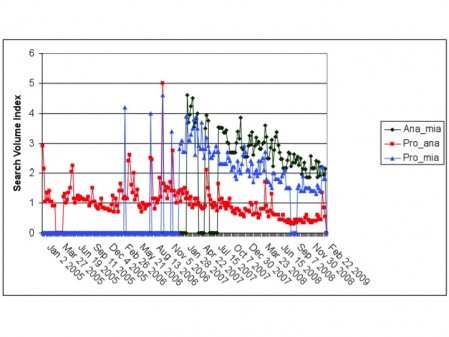

In the last years, the pressure on pro-ana has increased – both at country and service provider level. The first to ban these web pages were AOL and Yahoo, over the period 2001-2004. Can we quantify the actual evolution of the online community after that? Of course there’s no such thing as a national survey of pro-ana/mia website use. Exploratory webometric analyses might illustrate the rise of related search trends, but they hardly tell us anything significant about the actual number of ED-related blogs and websites (to say nothing about the Facebook groups and Twitter accounts). All they detect are peaks of interest for pro-ana news stories among the general public. Here’s the evolution 2005-2009 (i.e. the period following the first wave of pro-ana censorship) of the search volume index for common ana-mia queries (Source: Google Trends):

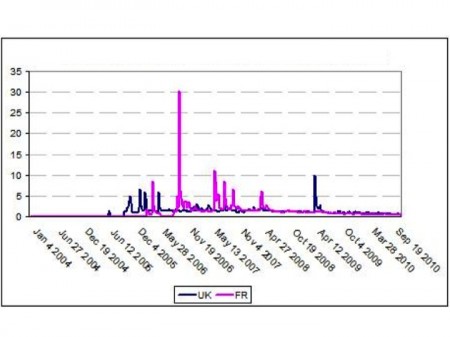

These figures are far from being a satisfactory approximation of reality. But they explain one important feature of the pro-ana-mia phenomenon: the first wave of censorship of 2001-2004 seems to have prompted not only a migration to other services but also a relocation to other countries. If at the beginnig of the 2000s, the pro-ED websites were mainly known in the US, by mid-2000s they had gone global. Let’s focus on France and UK, two countries that since then have been actively trying to put into place restrictive legislations on pro-ana (respectively in 2007 and in 2008). Providers have increasingly denied domain hosting, blogging platforms have shut down individual pages, Facebook has unplugged groups and Google has ostensibly limited pro-ana search results. As a consequence, after the spikes of 2007 in France and of 2009 in UK, the search volume index for “pro-ana” in the countries was soon reduced to a crawl in the following years (Source: Google Trends):

Mapping ‘ana-mia’ networks

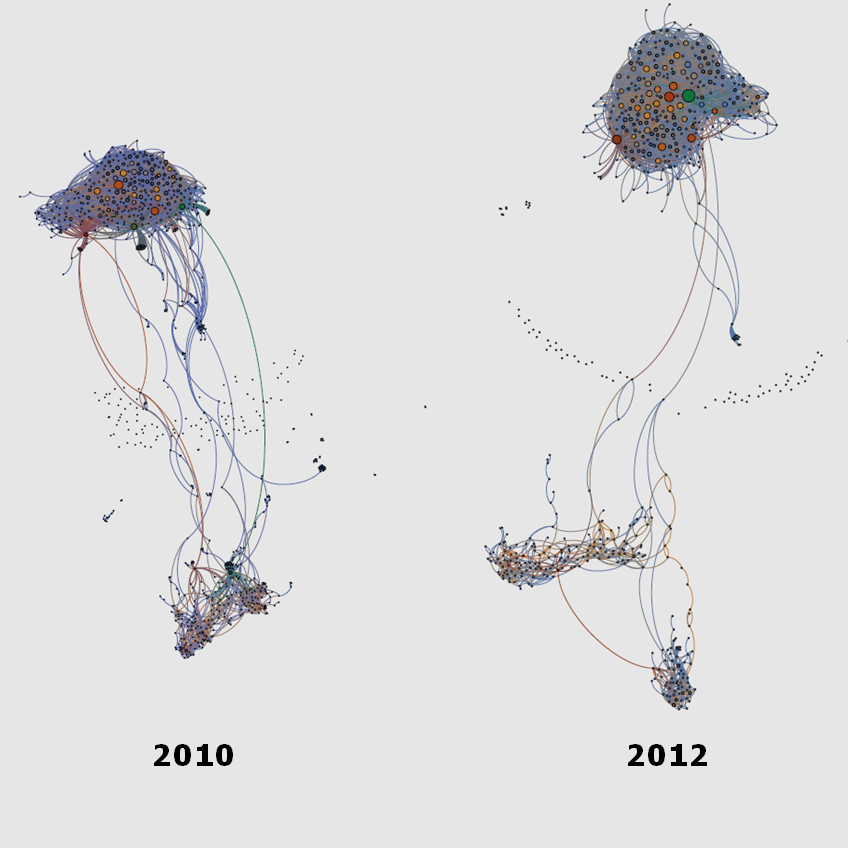

This doesn’t mean that the pro-ana-mia blogs, forums and online groups have disappeared. If, instead of trends we focus on the structures of online networks, we see a different picture. It seems censorship doesn’t affect the size, but rather the shape of the social graph of the online ana-mia community. To illustrate this, using Navicrawler we explored the French ana-mia blogosphere at two different dates (March 2010 and March 2012). The idea was to try and understand where so-called pro-ana Web pages are located and how much they are interlinked. Here is a visualization obtained with Gephi:

Mapping pro-ED websites (France, 2010-2012) – ANAMIA Research project

Mapping pro-ED websites (France, 2010-2012) – ANAMIA Research project

How can we read this graph? First of all, despite the legal pressure to ban ana and mia websites the network has not become smaller. The number of nodes (referenced pages) was 559 in 2010. It is 593 in 2012. Again, these figures are crude approximations. Assessing numerically this ‘invisible Web’ is highly problematical. Plus, crawling is a tool meant to explore, not to produce exhaustive representations or statistically representative samples. Let’s just say that the network is certainly consistent from year to year – and comparable to the figures of the English-speaking Web ten years ago.

Sizable clusters are discernible at the top and at the bottom of the two graphs. These are communities hosted on popular blog platforms and rallying around influential individual blogs that act as hubs (the bigger nodes). The main difference from year to year is that there are fewer and fewer links bridging the gap between the top and the bottom of the graphs. Accordingly, clusters gain strength: a brand new one adds up, as the other two become denser, larger, more interlinked and they attract isolated Web pages.

This is a clear illustration of the toothpaste tube effect: it seems that legal pressure has “squeezed” the network in its middle, like one would do with a toothpaste tube. As a consequence, blogs are extruded to the margins (top and bottom) of the graph. All censorship does is reshaping the graph. But not always the right way.

Why pro-ana censorship is bad news for public health policy-makers

By forcing blogs to converge into one of the bigger clusters, censorship encourages the formation of densely-knitted, almost impenetrable ana-mia cliques. This favours bonding, but also information redundancy – meaning that pro-ana-mia bloggers will tend to exchange messages, links and images among themselves and to exclude other information sources. Imagine you are a medical institution trying to put in place an information and awareness campaign on the risks of extreme fasting or exercise. Because of the toothpaste tube effect, it is clearly more difficult to reach out to ana-mia bloggers now than two years ago. If in 2010 a public health information campaign would target the Web sites in the middle of the graph and hope they relay the message to the margins, in 2012 the middle is virtually deserted. The only option is to cut through the dense clusters and hope your message will reach one of the more central influencers. But this is clearly a long shot. Ana-mia Internet users are constantly putting in place new strategies to elude general public visibility. Websites use cryptic language, password protections, and special software applets to circumvent search engine indexing. For these sites, censorship is a risk they have to constantly manage by fine-tuning their visibility.

Because of the toothpaste tube effect, we can conclude that all censorship does is to relocate ana-mia forums and blogs, moving them onto other platforms or to other countries, remodelling their social network in denser and more disconnected clusters. Those who actually suffer the consequences are healthcare professionals, public decision-makers, families and charities providing information and support for people affected by eating disorders – but not for ana-mia online communities. They know how hard it is to reach out to ana-mia online communities, and they know that it will be increasingly hard if these communities become more suspicious, secluded and inward-oriented.

[This post was made possible by the help of the fine people at the ANAMIA research team: Paola Tubaro (SNA coordinator), Fred Pailler (graphs and analyses), Débora de Carvalho Pereira and Manuel Boutet (webcrawling). The research project is funded by the French Agency for National Research (ANR) under grant agreement n. ANR-09-ALIA-001. ]

—

[↩] ADDENDUM April 5th, 2012: Upon reading this post, French academic blogger @affordanceinfo (Olivier Ertzscheid) asked whether there is a difference between the toothpaste tube effect and the Streisand effect. In both cases, information censored on one Web site or service is mirrored elsewhere in an incontrollable manner. There are, nevertheless, two main differences. The first one is the role played by the source of the information. The toothpaste tube effect concerns documents (texts, images, etc.) willingly put online by a source and censored by a third party. On the contrary, the Streisand effect concerns contents that are leaked by a third party, against the will of the source that actively tries to censor them. A second – and most important – difference is the outcome. By making contents and sources converge to specific zones of the Web, the toothpaste effect produces network density and bonding. Ultimately, censorship creates or reinforces a common identity. On the contrary, the Streisand effect produces virality, i.e. an ephemeral circulation of information in sparsely knit, dispersed networks. Given the perfunctory nature of the information exchange, the Streisand effect, is unlikely to create or reinforce a common identity.