The French translation of this essay is available on OWNI (part 1 and part 2), as installments of my column Addicted To Bad Ideas.

With the new academic year kicking in, my colleagues and I have decided to add a little wiki twist to a couple of courses we teach at Telecom ParisTech. I started a Wikispace for my digital culture class, and with Isabelle Garron and Valérie Beaudouin we’ve made compulsory for first year students to try and edit and discuss at least one Wikipedia page, as part of their initiation to online writing.

Sure, Wikipedia has been used as teaching tool in academia for some years now, to say nothing about its increasing popularity as a research topic. But the main rationale for using it in the classroom is that it has become the one-stop-shop for bibliographical research and fact-checking.

Challenging the Academic Mindframe

Think about your own online information habits. What do you do when you don’t know the first thing about a given topic? You probably google it, and the first occurrence is most likely a page from Jimbo Wales’s brainchild. You do it, we do it, our students do it. So we have to incorporate Wikipedia in our academic activity, not because it’s a cool gadget, but because otherwise it will create a dangerous blind spot.

[Don’t panic… Ok, panic]

And yet, admitting to this without panicking is not simple. At least here in continental Europe, ill informed judgments about the allegedly poor quality of Wikipedia articles are still commonplace in higher education. Some – like the French high-school teacher Loys Bonod, who had his 15 minutes of fame earlier this year – go as far as to add false and misleading information to Wikipedia, just to demonstrate to their students that it… contains false and misleading information.

Such paradoxical reactions are a case in point. Wikipedia is just as accurate and insightful as its contributions. Hence, the need to encourage its users to relinquish their passive stance and participate, by writing about and discussing relevant topics. Of course, one might say, when it comes to Wikipedia the Internet iron law of 90–9–1 participation applies: for 90 simple readers of any article, there will be only 9 who will make the effort to click on the “modify” tab to actually write something in it, and maybe just 1 motivated enough to click on the “discussion” tab and start a dialogue with other wikipedians.

Social scientists can come up with many explanations for this situation. The claims about the dawn of online participatory culture might have been largely exaggerated. Or maybe the encyclopaedic form tends to recreate cultural dynamics that are more coherent with an “author vs. reader” dichotomy than with many-to-many communication. Or maybe Wikipedia editors tend to intimidate other users in an effort to increase their own social status by implementing specific barriers to entry.

Try starting a new article. In all probability, its relevance will be challenged by some editor. Try starting the biography of a living public figure. Chances are that a discussion will ensue, focussing not on the public figure in question, but on the private qualities of the biographer. Is the author just an IP-based anonymous, or a legit logged-in user with a recognized contribution track record?

This is true for pages about living persons, but, as I have personally witnessed, for dead people the situation might become tricky as well. On November 3rd, 2009, 3:34 PM, via an academic mailing list, I received an email from the president of the institution I happened to work for at the time. The email stated that, “aged 100, our colleague, Claude Lévi-Strauss had died”. Assuming that the news was first hand, appealing to the larger public and coming from a reliable source, I decided to put it on Wikipedia. So I edited the page “Claude Lévi-Strauss” introducing the date of his death. I didn’t bother logging in: I was assuming my IP address (I was writing from my office) would somehow vouch for me.

But as soon as I clicked on Save changes, a message popped up on my screen warning that my IP address was recognized as one of my academic institution and was thus considered suspicious. An editor would have to validate my edits. And the editor did not: he or she dismissed the piece of information as unsubstantiated. The “appeal to authority” (me writing from the very same institution where Claude Lévi-Strauss had taught) didn’t seem to count. The page was eventually modified soon afterwards by somebody who made the correct link to the newswire of the Agence France Press.

[Screenshot revision history of the Wikipedia page Claude Lévi-Strauss]

This makes for a compelling example of how intellectual authority is reshaped in open knowledge environments such as Wikipedia. The academic ex-cathedra (in this case we might say the “ex-IP address”) attitude is questioned, in a healthful – yet frustrating for academics – way. What is at stake here is not only the intellectual status of academic institutions today, but the way information is validated.

The Hell of Notability

Remember seeing a banner on some Wikipedia page warning that its “neutrality is disputed”? In a sense, every Wikipedia page should display it, as every article is a small controversy in itself. Its authors struggle over the way topics are developed, pigeonholed, referenced. They struggle over the addition of external links or the spelling of words. Most of all, they struggle over what topics are suitable (or “notable”) for inclusion. Over the years, these arguments have become so frequent that Wikipedia had to come up with its own notability guidelines and with a list of AfD (Articles for Deletion) updated everyday.

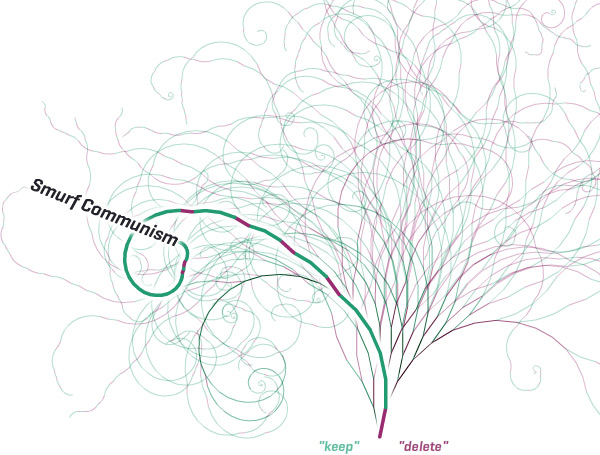

Some illustrious Wikimedia analysts have imagined a simple and elegant way to appreciate the controversial nature of these articles. Notabilia is a visual tool that aims to detect idiosyncratic discussion patterns resulting in “Delete” or “Keep” decisions. Extremely controversial discussions, where users opposing an article disagree with users defending it, tend to draw a straight line, as contrasting opinions balance each other. On the other hand, when there’s total agreement among participants about whether to keep or delete a page, the pattern gets curly, as the discussion “spirals up” to a settlement.

[The downward spiral of Smurf Communism…]

The meaning and impact of such open discussions among Wikipedia contributors highlight a vibrant community coming together around specific topics. Actually, one might say that Wikipedia is just another social networking site. Its users display their interests on their profiles like on Google+, they win badges like on Foursquare, they discuss publicly like on Twitter, their privacy is practically nonexistent – like on Facebook.

[A random Wikipedia user profile]

In principle, this structure allows arguments to be worked out and factual errors to be reported, promptly and transparently. But it also introduces a distinctive element in the information validation process. Trust and social support Wikipedia authors manage to build, greatly impact the perceived quality of their articles. In this, like in many other epistemic communities, trust is contextual. It depends on the networks of contacts an author can elicit. Ultimately, according to some authors, trust in Wikipedia is a by-product of users social capital, rather than the outcome of their competencies and knowledge 1.

An example, that I already discussed in my book Les liaisons numériques. Vers une nouvelle sociabilité ? (Editions du Seuil, 2010), might illustrate this particular point. On February 2009, a controversy regarding the article “Precarity” erupted on the English Wikipedia. In social sciences, precarity is defined as the set of material conditions of temp workers in postindustrial societies. The notion has been developed by several autonomist marxist authors, like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. The article was thus filed under “Organized labour”. But an anonymous Wikipedia contributor, swiftly dubbed “the catholic”, had a somewhat different opinion. He insisted that “precarity” was first introduced by a French monk who used the term to describe the fragility of human existence facing God’s transcendence. His point was accurate, and duly documented. But instead of defending his position in the discussion page, he unilaterally proceeded to place the whole entry under the category “Social christianity” and defuse all references to unionism and syndicalism. In next to no time, a furious battle broke out. Each night “the catholic” would classify the article under Christianity; each morning the marxists would protest vehemently and place it back under Labour.

This is where I, like many other wikipedians, started wondering whom to trust. I conceded that the anonymous catholic author had a point, but I lined up with the autonomist marxists, and provided my reasons in this Nettime post: the article was to fall into the Labour category to optimize searchability. I believe I was not the only one to adopt a non-academic stance at that particular moment. Wikipedia does not aspire to an all-encompassing accuracy, but to a consensus. Although many a wikipedian will claim that their online encyclopaedia “is not a democracy”, much of their decision-making process is in line with theories of democratic deliberation 2. And in this case, as partisan polarization was keeping the article on hold, a simple majority rule was to be applied.

THE VANDAL AND THE WIKIPEDIAN

Wikipedia disputes cast the shadow of vandalism. In the previous example, before a solution was found, the catholic contributor was accused of “usurping”, “defacing” the article. In order to put a stop to his edits, the marxists filed a semi-protection request, de facto equating all expressions of dissent to an act of vandalism. I was not comfortable with this solution, yet I was not surprised. These are common accusations in the Wikipedia scene. Some of the disagreements simply cannot be settled publicly. When opinions are over-polarized, behaviours become violent and negotiation fails and rival vilification starts.

“When tensions and conflict escalate and do not manage to “shift” into a reasoned discussion, it seems that the method adopted by Wikipedia consists in trying to “blame” a person, allegedly acting as a troublemaker or a vicitimizer, for the situation getting out of control.” 3

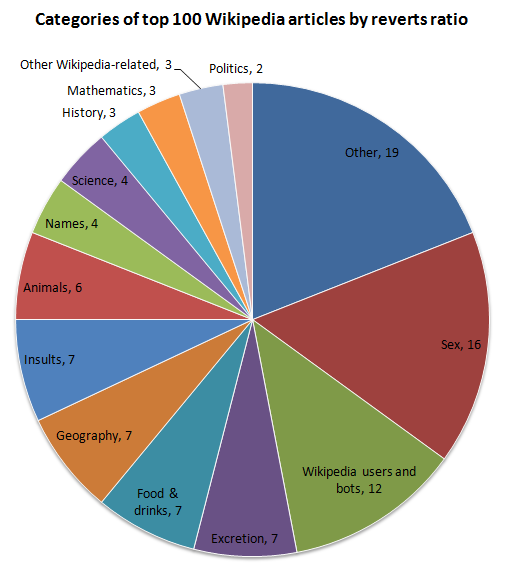

In 2010, a database of the most “reverted” English Wikipedia pages was released on the Wiki-research mailing list. “Reverts ratio” (i.e. the ratio of invalidated changes to a certain article over the total number of revisions) is a reliable indicator of vandalism in Wikipedia. A quick analysis provided a good insight as to who vandals are.

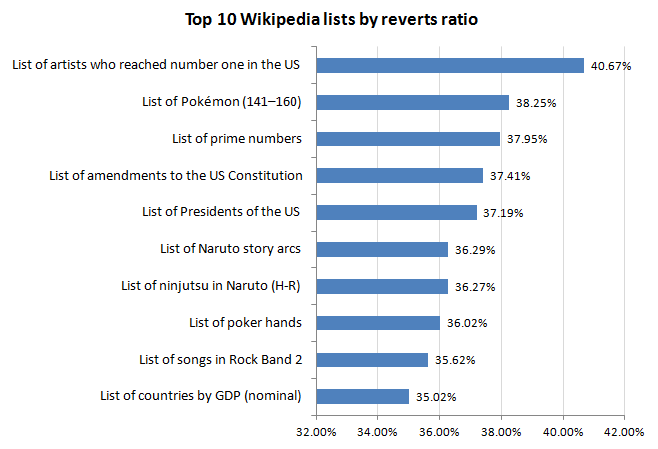

The target pages fall in some predictable categories, like sex (16%), excrements (7%), and insults (7%). The kind of juvenile humour which would lead us into thinking that Wikipedia vandalism is circumscribed to teenagers and young adults. And the fact that the years 1986-1992 are the most “reverted” seems to corroborate that, too. Apparently, people have a strong urge to vandalize their year of birth… True, among the main targets we find such articles as « Incas » or « Italian renaissance ». Hardly the objects of toilet humour, these topics help us formulate another hypothesis: vandals’ cultural interests converge on contents they happen to browse while trying to copy and paste stuff for their homework. There is a link between the rowdy behaviour of those 18-24 year-old Wikipedia users and a certain brand of school and academic socialization.

Which brings us to another clear result. Among all the English-speakers, the highest concentration of disruptive contributors (as far as their number is proportional to articles with higher revert ratios) is in the US. ‘America’ is the number 1 vandalized article for its category (40.9%). 9 over 10 of the most vandalized articles dealing with battles, touch on historical events that took place inside the US or Canada borders. Some of the most targeted “talk pages” are those of North-American celebrities (Zac Efron, the Jonas Brothers…) and historical figures (Benjamin Franklin, George Washington…).

So who are those Wikipedia vandals? Their portrait is shaping up: they are young, aware of all things American and, well, quite geeky on the side. They browse through science and maths portals rather than humanities. They struggle over establishing lists of topics such as cartoons, video games, prime numbers, and so on.

How do we make sense of these results? The English Wikipedia article Vandalism puts a lot of emphasis on Pierre Klossowski’s argument that sabotage might be regarded as a cultural guerilla of a sort against an oppressing intellectual hegemony. Vandals are, and I quote, “only the reverse side of a criminal culture”. Yet this notion of “reverse side” – though conceptually linked to that of “revert ratio” – does not only signify a dialectical opposite, but also a mirroring image of the general consensus that Wikipedia articles are built upon. In a sense, the vandals – as a group contributing in their own disruptive way to the social construction of knowledge in the popular online encyclopedia – can and must be considered as a reflection of the wikipedians as a whole.

By way of conclusion, I’d like to make an educated guess that the cultural concerns, demographic composition and interests of users performing vandalism are not that dissimilar from those of regular contributors. If, as Michael D. Lieberman maintains 4, Wikipedia users reveal their interests, geographical coordinates, and social connections through their contribution patterns, so do their vandal counterparts. This list of most reverted articles might help us see how vandalism builds up over topics, how it is structured, hence providing a useful portrayal of the cultural interests (and of the corresponding cultural biases) of the entire Wikipedia community.

Vandalism do not necessarily represent an anti-culture fighting against a power elite of system administrators and vigilante editors. We can agree that Wikipedia, more than other encyclopaedic projects, encourages reflexivity insofar as it shows that knowledge is not a collection of notions, but a collaborative process in the making. Several actors take part in this process and contribute to this reflexivity through negotiation, controversy, advocacy, and (in my opinion) vandalism. Undoubtedly, the role of vandalism is usually overshadowed by pro-social behaviours. But in fact vandalism stimulates pro-social behaviours.

Consider this: an average Wikipedia disruptive act goes unpunished for as little as a minute and a half 5. After that short lapse of time, defaced articles will likely catch the eye of a few editors, who will likely revert them to their previous form and put them on their watchlists. Maybe at this point the vandals will stop. Or maybe they’ll continue. Anyway, they have put the targeted articles on the editors’ radar. They have forced other Wikipedians to react, correct, focus. Ultimately, vandals accomplish the essential function of eliciting other users “participatory vigilance” 6. By their mischievous edits, they revive the attention for long-established topics, boost sleeping discussions, stir up awareness. Thus, they achieve the ironic result of furthering cooperation via abuse, participation via contrarianism – and knowledge via ignorance.

- K. Brad Wray (2009) The Epistemic Cultures of Science and Wikipedia: A Comparison. Episteme, 6 (1): 38-51. ↩

- Laura Black, Howard T. Welser, Jocelyn DeGroot & Daniel Cosley (2008)’Wikipedia is not a Democracy’: Deliberation and Policymaking in an Online Community. Paper presented in the Political Communication Division of the International Communication Association annual convention, Montreal ↩

- Nicolas Auray, Martine Hurault-Plantet & Céline Poudat (2009) La négociation des points de vue : une cartographie sociale des controverses dans Wikipedia francophone. Réseaux, 27 (1) : 15-50. ↩

- Michael D. Lieberman & Jimmy Lin (2009) You Are Where You Edit: Locating Wikipedia Contributors through Edit Histories. ICWSM, AAAI Press ↩

- Viégas, Fernanda B., Wattenberg, Martin and Dave Kushal (2004) Studying Cooperation and Conflict between Authors with History Flow Visualizations, CHI 2004, 6 (1): 575–582. ↩

- Dominique Cardon & Julien Levrel (2009) La vigilance participative. Une interprétation de la gouvernance de Wikipédia, Réseaux, 154 (2): 51-89 ↩