Le sociologue Antonio Casilli, auteur de Les liaisons numériques. Vers une nouvelle sociabilité ? (Ed. du Seuil), est l’invité de Impact of Social Sciences de la London School of Economics. Le prestigieux blog anglophone héberge une tribune sur le rôle des médias sociaux et des TIC pour contrecarrer le processus de prolétarisation des professions scientifiques qui touche tout particulièrement les sciences sociales.

By leveraging social media for impact, academics can create broader support for our intellectual work and profession.

cademics have a chance to make a ‘social impact investment’, by introducing the greater public to our work and bypassing the bottleneck of commercial publishers but only if we scrap our social media-shy ways, writes Antonio Casilli.

In the latest issue of the online journal Fast Capitalism, an article by Jessie Daniels and Joe Feagin provides an insightful take on the issues faced by an increasing number of researchers in social sciences who are struggling to include social computing in their repertoire – and to leverage it in their CVs. The advent of participatory Web in the academe is sure accompanied by a techno-utopian discourse of increased opennennes, collaboration and democratization of knowledge.

Although these beliefs almost verge on common sense, in sociology and neighbouring fields academic social media use meets mixed reactions. It is still perceived as a side activity, potentially distracting scholars from their career-building tasks: journal articles, empirical research, teaching, etc. How can prolific academic bloggers, active Wikipedia contributors or Facebook community managers properly draw upon the efforts they deploy in their online contributions, and turn them into scientifically and socially impactful achievements?

Of course, not everyone is in the same position. Our occupations are contextual to who we are, which institution employs us, and where we are on our career path. For untenured scholars, for instance, being online can turn out to be risky – almost an “extreme sport”, some scholars insist: too much exposure and opinion-sharing might alienate people who can potentially get you tenure. And assuredly, for both tenured and untenured scholars, contributing to online publications and social media is time-consuming.

These concerns pertain to any academic field. But how do they apply to social sciences in particular? Indeed some disciplines were quicker than others to understand the potential of social computing, and make the most of it for scientific impact and visibility purpose. Think digital humanities, and the methodological and epistemological shift they recently came to represent. Social sciences didn’t develop at the same pace. That’s why today digital sociology is not an organized, recognizable, and well-funded research field.

Sociological inertia?

Partly, professional inertia might explain that – and in this case our focus should widen to include computing at large, not only online social computing. In a 2010 article Dan Farrell and James Petersen describe what they dub the ‘reluctant sociologist problem’: despite the pervasiveness of ICTs in every aspect of contemporary social life the very investigators of social realities are yet to fully embrace digital methods. “Between 1999 and 2004, only one article appeared in the American Sociological Review, the American Journal of Sociology, or Social Forces using primary data collected with Web-based research techniques. Since then there have been only a handful of studies published in these core sociology journals drawing on Web-based surveys or other forms of Web-based data”. Their concern echoes Paul DiMaggio’s and Eszter Hargittai’s early admission that, though critically important for their research, the Internet has been slowly taken up by sociologists as an object of study

The fact that these two articles are separated by almost ten years brings the point home: maybe sociologists do not like to include technological competencies and new notions to their skill set. Maybe it’s a classic case of teching an old dog new tricks. Except the dog is not that old – sociology was created less than two centuries ago. And the trick is not that new either. At least since Semen Korsakov invented his homeoscope (« machine to compare ideas » ancestor to our search engines) in 1832, information technologies have been successfully embedded into social sciences for documentation and data treatment.

Actually, different branches of sociology are differentially concerned by the digital shift. One way of problematizing the loathness of the “reluctant sociologists” to adopt technologies would be to point at a subset of the field, namely “soft” social sciences, involving more qualitative and theoretical approaches. Computing for information processing has long been customary for “hard data” sociologists, like those in the burgeoning subfields of social simulation, social network analysis or the sociology of controversies, heavily relying on computational methods. “Soft” sociology, on the contrary, doesn’t seem to have the same ease with ICTs or – when it has – it’s still way too exotic to be representative of a new trend in the respective research areas.

Though this differentiation might seem plausible, it would be conceptually inaccurate to hold one part of sociology responsible for the supposed inertia in adopting computing-intensive approaches. In fact inertia might not be the reason for the present state of affairs to begin with.

Unrealistic representations of academic labour market structure are holding back digital sociology

We need to go back to Daniels and Feagin article, where they suggest a possible line of explanation by looking at the way digital production of knowledge goes unrecognized by tenure and promotion review committees. Broadly speaking, authors insist, academic recruitments and career advancements in the field of sociology are less – if at all – keen on computational achievements when evaluating their candidates. This would not be the case in neighbouring disciplines.

So when we ask what’s holding back digital sociology, the answer is that there is definitely a job market dimension to this hesitant attitude. And this is true for both “soft” and “hard data” sociology. The former doesn’t have an incentive to include computational achievements in their academic repertoire; the latter doesn’t need to have them recognized because, as said supra, they are already an integral part of the trade.

Indeed, this disinterest can also be considered as an effect of a biased collective perception of the dynamics of academic labour market for social science disciplines. Unlike other endangered disciplines heading towards a “jobless market” social scientists do not necessarily perceive the urge to foster the impact of their research via social computing.

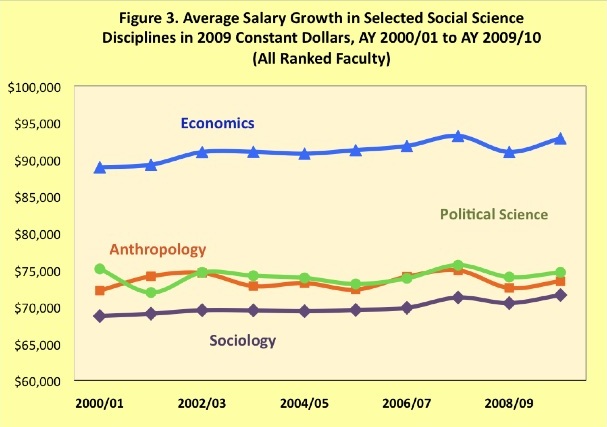

In recent years higher education professional and academic associations have possibly played a role in lulling the labour force in a false sense of economic security. The annual reports of the American Sociological Association, to take one well-known example, are bewilderingly reassuring: over the last decade, sociology salaries increased, or rather not, if calculated in constant dollars, “but they still outpace inflation.”

Of course, unemployment and faculty salaries are not the only indicators of the effects on academe of increasing economic and managerial pressure. The proletarization of academic labour force is a more creeping feature of contemporary job market. To quote Andrew Ross, it mainly manifests via “the creation of a permatemps class on short-term contracts and the preservation of an ever smaller core of full-timers, who are crucial to the brand prestige of the collegiate name. Downward salary pressure and eroded job security are the inevitable upshot”.

Nevertheless since 2000, the number of adjunct sociology faculty either decreased or remained the same in most departments . That is in strident contrast with analyses emanating from other research and education agencies. In 2003, Marc Regets, senior analyst at the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) was still tentatively asking if postdocs were to be regarded as an industrial or academic “reserve army” of unemployed PhDs. Since then, the number of underpaid, defenceless, precarious postdoctoral fellows in social scienses doubled, and that of non faculty research staff has tripled.

Can digital sociology help counter the proletarization of social sciences?

In the light of these facts, what is the the role of digital sociology? At first sight, it might come to be regarded as an accessory to the growing fracture within the labour force, between tenured and untenured academics. On the one side, the reserve army of postdocs and adjuncts, for whom social computing entertains the perspective of accessing tenure by boosting their impact via online professional networking; on the other side, the faculty members for whom digital methods are either trivial (“hard data” sociologists) or useless (“soft” sociologists).

But before dismissing digital sociology as a ruse of market flexibility, there is another way of envisaging it as a site of struggle and resistance. If we move away from a merely desciptive posture, and stop spying for signs of acceptance or opposition to digital methods in social sciences, we might adopt a more proactive stance. The social Web can be an way of creating significantopportunities for engagement that can challenge academic managerial and institutional models. Recent whistleblowing initiatives, such as Unileaks or crowdsourced e-books such as Hacking the Academy are to be regarded as good instantiations of this possibility. Online social media presence as well as a more computer-savvy approaches to teaching and research might be valuable ways to circulate information, compare practices, raise awareness, foster respect inside and outside the sociological community.

I would like to add that, if digital sociology can be regarded as a means of academic industrial action in the present economic juncture, it is only by promoting long term scientific and pedagogical impact that it can actually be decisive in avoiding the proletarization of academic labour.

First of all, by providing open, alternative venues for scientific publication online, it can help bypass the bottleneck created by commercial publishers. Secondly, and most importantly, social media and online press can play a essential role in eliciting sociological vocations in the next generations of students. By contributing to a wider, inclusive public debate touching on societal issues, by engaging in substantive exchanges of ideas both with non-specialists or specialists from other disciplines – in a word, by scraping their (social) media shy ways – they can familiarize a growing number of perspective students with the methods and research questions of social sciences.

Consider that as “social impact investment” for our future research and teaching, whose outcome will not be academic prosperity via increased revenues from graduate student fees, but a broader social support for us and for our intellectual worth as a research field and as a profession.